Architects and designers are raising the bar of what sustainability means by pursuing building projects with little to no carbon footprint in response to the growing concern around climate change. Six hundred firms are now a part of the 2030 challenge, an industry initiative to design buildings both new and old as carbon neutral (i.e. their emissions are either reduced or offset until the net result is zero).

Here, we look at four firms driving the vision of good, future building design through innovation, sustainability and renewable energy.

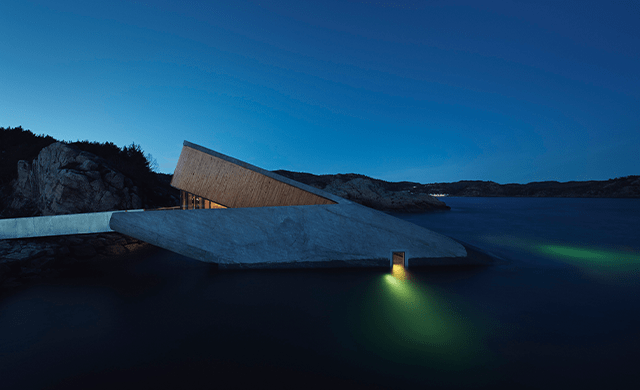

Snøhetta

The Snøhetta-designed Nordic restaurant Under, one of its Powerhouse projects, opened last year.

Oslo-based multidisciplinary firm Snøhetta envisions the future of sustainable design in its Powerhouse Brattørkaia. Nearly 33,000 square feet of solar panels blanket the upper façade and steeply angled pentagon-shaped roof, which is designed to capture as much daylight as possible. This way, the central Norway complex will produce far more clean electricity than it will consume with the goal of cancelling out over 60 years of carbon emissions produced during its operations as well as those produced during construction.

Not only that, the Powerhouse standard is also used by Snøhetta and others within the industry to identify ultra-efficiency in projects. The Svart hotel, for instance, aims to reduce its energy consumption by 85 percent in comparison with new hotels and “exceed carbon neutrality” according to Aaron Dorf, a director at Snøhetta’s New York office.

HOK

The New York-Presbyterian David H. Koch Center features a triple-paned glazed façade.

Anica Landreneau, who leads HOK’s sustainable design initiatives, says that modeling how, where, and when buildings consume energy is the to better targeting green design initiatives.

Take the Royal Caribbean office: a boomerang shaped building that allows daylighting across a higher percentage of its floor thanks to its shape, with overhangs that considerably cool the building, thereby reducing modeled cooling costs by as much as 13 percent. The David H. Koch Center in Manhattan, meanwhile, has triple-paned insulated glazing with a slatted wood screen, reducing solar glare and cooling the building while providing privacy shading.

The biggest challenges to carbon neutrality, Landreneau says are the extra costs, complexities and client preferences associated with projects. But that has not slowed the firm down. Since joining the 2030 Challenge, HOK has achieved about a 60 percent reduction in its portfolio’s predicted energy use.

Mikhail Riches

Goldsmith Street residences feature timber frames and walls filled with recycled newspaper.

After winning the RIBA Stirling Prize for its latest project, Goldsmith Street, London studio Mikhail Riches vowed it would work only on zero carbon projects going forward. The project itself, a low-rise, high density development in Norwich, England, is the largest UK project to meet Passivhaus standards, a voluntary initiative for ultra-low energy consumption in buildings.

“As architects, we have a chance to be leaders in this field, and as eternal optimists, we see this as an opportunity to develop new design approaches,” says Oliver Bulleid, director at Mikhail Riches.

For Mikhail Riches, that started with focusing on reducing energy usage from building operations like heating and water. Now, the firm’s architects are directed at curbing emissions via construction materials, taking inspiration from the way in which some older buildings are constructed with locally sourced materials. According to Bulleid, the firm is finding that well-designed, low-energy projects often cost only slightly more than those meeting minimum sustainability standards.

As more public officials call for net-zero building initiatives, Mikhail Riches is partnering with authorities to help create more affordable, sustainable communities. Clay Field, for instance, an affordable housing complex in Suffolk, uses sustainably grown timber and is insulated with a mixture of hemp and lime to trap carbon in place instead of releasing it into the atmosphere.

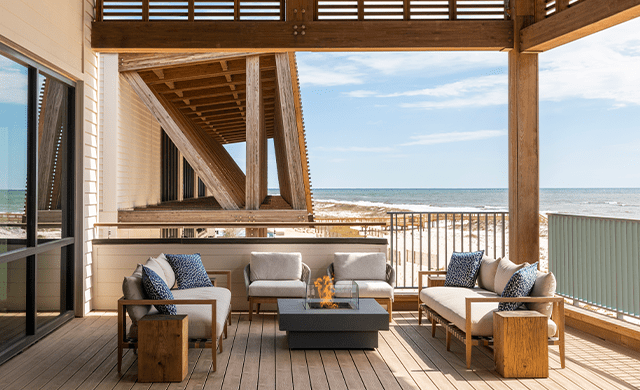

Lake Flato

Guestrooms at the Lodge at Gulf State Park are equipped with operable windows.

Texas architecture firm Lake Flato strives to design buildings that reflect the local culture and climate. And increasingly, the firm has been focusing on measuring and understanding the embodied carbon in construction materials.

For Bunkhouse Group’s Hotel Magdalena in Austin, Lake Flato’s architects opted to use mass timber—engineered wood products with a lower-emissions profile that lock carbon in panels, posts, and beams. The 47,000-square-foot property will be the first mass timber boutique hotel in North America upon its completion this spring.

Then at Hilton’s the Lodge at Gulf State Park in Alabama, the firm found additional ways to reduce the project’s footprint. Each guestroom has operable windows directly tied to thermostats, so guests can naturally ventilate their rooms without heating or cooling systems. The hotel also captures condensate from air-conditioning units, which fills up the swimming pool to reduce the use of potable water.

Heather Holdridge, sustainability director and an associate partner in the firm’s San Antonio office, says her team has learned that carbon-neutral buildings can’t exist without carbon-neutral occupants. “They need to understand how their behavior impacts it,” she says. “You have to have the owners and users engage with that goal.”

Another version of this article previously appeared in Hospitality Design.